- À New Wave to Fashion, À New Way of Living. Download Now on iOS Android Canada SS22

- hello@alahausse.ca

A Profile on the Environmental Impact of Wool

The Dirty Little Secret Behind Cotton

February 20, 2021

The Capsule Wardrobe – ÀLA.HAUSSE’s Sustainable Approach to Closet Management

February 26, 2021

Written by: Sheila Lau

With people becoming increasingly aware of how the fashion industry contributes to environmental pollution, more and more consumers are turning to plastic-free clothes made of natural fibers. This has led to pushback against synthetic fibers like nylon, polyester, and acrylic. Instead, the fashion industry is looking to use more sustainable materials, like cotton, wool, hemp, and bamboo. But, solving the fashion industry’s pollution is more complex than just buying plastic-free.

In the first part of our natural fiber series, we examined the environmental impact of natural and organic cotton (you can read about it here). This week, we will be looking at wool and its eco-footprint.

The Eco-Friendly Aspects of Wool

As a textile, wool has a history dating back hundreds of thousands of years. This is with good reason. Wool is a natural protein fiber that comes from sheep fleece, and it is highly valued for its ability to retain heat. In recent years, the fashion industry is turning once again to this textile. This is not only because of its thermal qualities, but also because wool is an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic fabric.

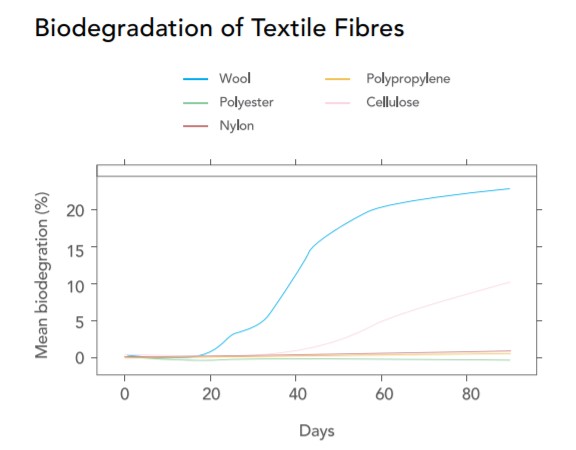

Unlike plastic fibers, wool is completely natural, renewable, and biodegradable. The International Wool Trade Organization (IWTO) reports that wool can completely degrade after 6 months in soil and within 1-5 years in marine environments. More importantly, because it completely degrades, it does not contribute to the 12.2 million tons of microplastic that enters our oceans every year. Instead, wool is readily compostable and can act as an effective fertilizer as it biodegrades.

Research shows that compared to other fibers, wool has the lowest water and energy use per wear. Because it is naturally stain and odour resistant, its clothing requires less washing, and when washed, it requires shorter and lower temperature laundry cycles. This means that woolen garments can last longer and require less replacement.

Polyester, on the other hand, requires frequent laundering and frequent disposal. This is especially true for those with sweat-resistant properties (like our yoga pants and athletic tops). The odour-causing bacteria sits on top of the polyester and the unpleasant smell clings to the fabric even after it has been washed. Because of this problem, the sportswear industry is turning to merino wool (aka performance wool) to make leggings, athletic tops, and even sneakers. For example, Allbirds make their sneakers from merino wool.

Wool is one of the best examples of a circular economy.

What does this mean? When woolen garments are disposed of, it can be remade into new yarn without a drastic reduction in quality. It can also be completely biodegraded in the compost heap and used as fertilizer. This means that wool remains useful, even when it is disposed of.

According to research by the Centre for Colour and Textile Science at Leeds University, wool is one of the most reused fibers. It accounts for 5% by weight of total clothing donated for reuse and recycling (a number that is much higher than the 1.1% share of wool in virgin fiber supply).

Wool can be recycled in three different forms. The closed loop system ‘pulls’ wool garments back to its raw fiber state, creating yarn that can produce new garments once again. The open loop system shreds garments into material used for industrial products, like thermal insulation, acoustic insulation, and mattress padding. And, last but not least, old or unsold garments can be re-engineered by companies into new products, such as creating a new bag out of an old wool coat.

The Environmental Problems of Wool

However, the production of wool is not without its problems. Like any textile that comes from livestock, a major concern is the land usage in its production. Some people are concerned that increasing production means more trees need to be cut down, more land needs to be converted into grazing lots, and more soil erosion will occur. Peta points to Patagonia, Argentina which was only second to Australia in wool production in the early 1900s. When the scale of the operations outpaced the sustainability of the land, soil erosion triggered desertification in Argentina.

Land use calculations in recent research have challenged these concerns. Although some studies report that the area of land grazed by sheep is large, it does not take into account that most land used by sheep is non-arable. This means that the grazing areas of sheep do not take up fertile land important for crops and trees.

More importantly, if more holistic land and livestock management is used, wool can even be “climate beneficial.” Rather than fencing sheep in the same pastoral lot to overgraze and erode soil quality, mimicking ancient grazing patterns by allowing sheep to freely range from paddock to paddock can actually remove carbon emissions from the atmosphere.

According to a study in the journal Soil and Water Conservation Society, herds that gently prune grasslands promote grass growth, churn soil, and fertilize the grasslands with their manure before migrating to a new area. Soil is the earth’s second largest carbon pool, so grazing actually allows carbon to be pulled out of the atmosphere and into the soil instead.

Animal Welfare of Wool Products

The largest area of concern in the production of wool is animal welfare. In conventional wool farming, sheep are “dipped” into insecticide and fungicide to keep pests from living within their skin folds and wrinkles. In Australia, where flystrike is common, a surgical procedure called “mulesing” is done to protect sheep from blowflies laying eggs on their skin. This procedure is painful both during and after the surgery, and is often done without anesthesia or post-operative pain relief. It involves the removal of skin flaps from a lamb’s breech and tail to create smooth scar tissue that blowfly can’t lay eggs on.

The IWTO reports that where possible, Australian producers have stopped using mulesing on their farms. In areas prone to flystrike, farmers are using more pre- and post-operative pain relief, or avoiding mulesing altogether by breeding sheep that are flystrike-resistant. For consumers and brands concerned about animal welfare, they can check the mulesing status of their wool through IWTO test certificates, or buy non-mulsed, merino wool from ZQ Merino.

The Verdict

Compared to other fabrics, wool is one of the best examples of a circular economy in the apparel industry. Not only is the source renewable, but at the end of its useful life, wool garments are fully biodegradable and readily recyclable. It can also be used for a longer period of time. The Centre for Colour and Textile Science at Leeds University shows that wool has an active life of 20-30 years, with the potential of two or more ‘lives.’

However, livestock management methods do need to be improved. More holistic land and livestock management of sheep can make our fashion “climate beneficial” by sucking out carbon from the atmosphere and into the ground. Using non-mulesing techniques can protect sheep from flystrike while also avoiding unnecessary pain.

For consumers and brands concerned about the environmental and animal impacts of wool, opting for recycled or reused woolen garments can minimize the direct impact on sheep and the land. This could mean buying from brands that make apparel with recycled wool fibers. Because wool tends to last longer than other fabrics, consumers could also choose to buy or swap a pre-loved wool garment through platforms like ÀLA.HAUSSE.

Via ÀLA.HAUSSE‘s Multi-functional and Multi-purposeful Fashion Ecosystem- BUY/SELL/RENT/LEND/ (swap BETA 2021) mobile application, INDIVIDUALS & brands ( BETA 2021) are encouraged to REBUY, RESELL, REUSE and UP-CYCLE their personal “Clossets” aka Clothing Assets, along with overstock inventory and samples. Through this consumerism habit shift we indirectly slow down the urgency on fashion’s carbon footprint, aiding sustainability as a whole.

BETA Early Access Application Now Open SS21 iOS Android

with Stories on www.alahausse.ca

#ALAHAUSSE #WEARYOURPURPOSE #HAUSSEPEOPLE